Pictured above is a photo of our 8- to 9-month old heifer named Hazel. Born on September 1, of 2022, she came to our farm just a couple of months later. I originally wanted a cow and calf pair, but the farm we bought her from didn’t have any at the time. They had the next best thing though—a grass-genetics A2/A2 Jersey heifer calf. In fact, their entire farm has been A2/A2 even since before A2 and grass-genetics were super “cool”.

We could talk about the A2 genetics, but that’s another topic for another day. Today, I’m talking about the grass-fed, small-framed genetics. Keep reading…

For a fraction of the cost of a cow in milk, or that is bred, we purchased Hazel for around $450. We paid a little extra to have her delivered since the farm was only 3 hours away, and we (at the time) didn’t have a truck in which to transport her. She hung out in a make-shift pen (at night), and on lots of hay and pasture, for the first six months of her life. With a mild winter, it didn’t matter what she was in. But we quickly realized she would need a barn, or at least a lean-to, if we were going to make this farm thing work efficiently. So we built a small barn.

Our goal with Hazel was to make her the best future family milk cow for our homestead, in temperament and grass-genetics. I needed a cow I could manage, not a cow that would manage me. Our hope was that we would eventually add the cow/calf pair we wanted from the same farm, or a different grass-fed dairy. We would have two milk cows that we would milk and offer herd shares to our community.

But something interesting happened—we boarded a friend’s beautiful full-sized Jersey in April of this year, and I realized this might be a little too much for our property, and my current season of life. One small, well-trained cow would be manageable, but two large Jerseys would be a different story.

We decided that maybe cows, in general, would be too hard on our almost 6-acre property. We had some pasture issues (though not awful), even though you can’t tell it from glancing over our pasture quickly. But we watched how much the full-size Jersey ate in a day, and we realized that this pasture just may not be able to keep up. Definitely not with two full-sized Jersey cows and their calves.

Deep down I knew that one cow, if smaller, would be fine. Maybe even two smaller cows. Definitely not full-sized cows. But I had no idea what the genetics of my sweet Hazel were, other than she was a grass-fed Jersey with the A2 protein. That doesn’t tell me much, though, about her size, her parent’s size, or even her grand-parent’s size.

In the meantime, we invested in sheep for dairy, because I assumed we’d have to get rid of Hazel based on our experience with the cow we boarded. But my local friends with Jersey cows kept saying, “you know, Hazel just seems so small for a Jersey, is there something different about her?” I assumed it was because she was bottle fed after the first two months of her life, albeit, with mostly raw milk. But then I remembered, “that’s right, she was bottle fed with raw milk, not milk-replacement”, and while being bottle-fed in general does slow down the growth of calves, she had an advantage—she was still getting the best milk option available.

So what was the difference between Hazel and these other heifers that were her age, yet towering over her? My mind instantly went to the worst—there must be something wrong. But truth overcame fear as I spoke to, and reminded myself of, the truths. She was healthy. Very healthy. She was converting grass well. She wasn’t eating all day long like a starved cow—she was taking very long breaks and resting, like a good, healthy cow should.

There really was something different about her. I knew I had bought her from a well respected grass-fed dairy. I knew that there were good genetics there, that’s the entire reason I held out for this heifer calf and decided to put the time into her. My husband will tell you, when I want good genetics, I wait for those genetics, or I make them happen myself (through breeding). Genetics, to me, have always been everything. No matter what livestock it may be.

Small Dairy Grass-fed Genetics

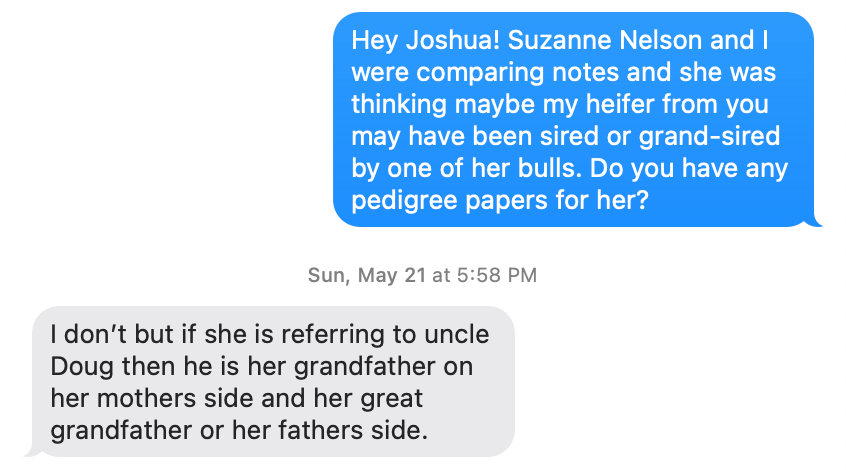

Enter side stage, Suzanne Nelson and Dr. Hue of Reverence Farms in North Carolina. I had been speaking to Suzanne for a few months now about other things. She had, however, told me that she thought Hazel’s genetics came from her farm, at least on her sire’s side. But still, I didn’t know what that meant. Not until we really got down to asking questions from the farm Hazel came from.

After texting Joshua (the farm Hazel came from), we got the answer we already kind of knew—Hazel’s genetics, indeed, came from the sire, Uncle Doug. Now, I don’t know much about Uncle Doug, the Jersey bull, but here’s what I do know from Suzanne about her bull….

“…that’s why she’s small framed! He definitely was, and line-breeding intensifies traits.”

This is exactly what I needed to hear! Just the previous day, Suzanne had posted on her Instagram page that she had mid-mini type genetics that she was breeding specifically for the homestead dairy. They were more manageable cows, yet still gave an extremely decent amount of milk. Suzanne also runs a grass-fed dairy, and genetics are also her passion. I’m learning lots from her.

Finally, I had the answer I needed and wanted—we could keep Hazel! In fact, we will keep her, and continue breeding these smaller-framed genetics with Hazel.

Are Genetics Really That Important?

I see quite an interesting trend in the homesteading community, and it’s not surprising. When we don’t want to pay for the work that others have put into good genetics, we make excuses as to why we don’t want to pay more for those genetics. Or, we make up things like, “grass-fed genetics are a myth” or a scam, or whatever other word you want to put in there.

Not wanting to pay more for something doesn’t mean that that something isn’t real. It just means you “won’t” pay for it, and that’s ok, too.

So the question is, are genetics really that important? The answer depends on the homesteader or farm. If you just want raw milk (no matter the protein), your land can support a full-sized dairy cow, and you are able to manage that animal well, then no, genetics may not matter to you. I would still suggest that you buy healthy genetics, not just the cull cows off of craigslist or at auction. Though, there are many people who have gotten fine cows off of craigslist or at auction—don’t misunderstand or misconstrue what I’m saying.

But what I am saying is, I see far too many homesteaders buying cheap dairy cows because “genetics don’t matter”, and they want an inexpensive cow. I can’t blame them. But unfortunately many think they are “bucking the system” or “sticking it to the man”, because everything is a scam now days, right?

Certainly some things are scams, or people taking advantage of others. For example, I enquired about an A2, grass-genetics dairy cow once and they told me they were asking $5,000 for her. No thank you, sir. Have you lost your mind? Currently, at the writing of this post, I see good A2 grass-genetic bred heifers or cows going anywhere between $1500 to $2800. Anything over that (right now), better come with a calf and have mama bred again.

Sometimes conspiracy mindsets are healthy, other times, they are detrimental and your homestead suffers over and over again. For me, I try to avoid that altogether. Does it mean it’s a failsafe? Not hardly. I’ve had moments when I thought I was buying great genetics with other stock animals and they turned out to be mediocre. But, with experience comes wisdom in knowing what to look and ask for.

For us, genetics are everything. I don’t want to spend years of my life trying to make something work that isn’t going to work. Unless, of course, I have a plan for that project, which is much different.

The health of your cow is always top priority, no matter what her genetics are. If you have to feed buckets of grain, feed grain. If you have to feed bales of hay more often than your neighbor because your pasture isn’t great, feed hay.

Amy K. Fewell | Homesteading for the Kingdom is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

But here’s the lovely thing about grass-genetics, they thrive on grass and hay. They don’t require grain to maintain weight, and really, grain isn’t the best way to “fatten up” any cow or livestock. Good quality free choice hay is your best bet there. Grain is used most often to give your cow more energy, which in turn helps the cow maintain weight.

Because Hazel came from a grass-genetics lineage, she holds her weight just fine on grass and hay alone. These are the genetics we needed for a more sustainable homestead. In the long-run, she saves me a whole lot of time and money if I continue breeding her to good quality genetics.

Little did we know, we would be getting the smaller-framed, more manageable genetics for our homestead as well. It was pure favor from the Lord, in this case. We weren’t even looking for something that we needed, because we didn’t even know it existed. But I truly believe the Lord knew, far in advance, what we would need.

You don’t know what you don’t know—this is a word the Lord has been speaking very prominently to me all year. The second half of that thought is, you do better when you know better. You breed better when you know better. You feed better when you know better. You become a better steward when you know now what you didn’t know before. We’re all on this journey together, and so, I’m sharing with you what I now know.

Are genetics that important? Maybe not for you, but they are for our homestead. We need good grass-converting genetics. We need genetics that are smaller-framed yet produce just as well. We need genetics that are healthy so we aren’t calling the vet every other month. In fact, it sounds like most farms would want this, right? But especially smaller homesteads that need to intently manage their grass.

Don’t be discouraged…

If genetics have never been your priority, don’t be discouraged. When you know better, you do better. Don’t get rid of that beautiful milk cow you have, just breed her to something better. Don’t covet the milk cow your online friend has, love the cow you have the best you can. She deserves it. And you’re still responsible for her good health. You’re still responsible in stewarding her. She’ll produce for you, giving you fresh milk every year. And she may even produce exceptional offspring for you.

But, if you feel as if you bought an unhealthy cow that you’re constantly pouring money into, it may be time to consider culling. If your cow is that bad off, you may even just consider culling by way of beef. This is where we have to decide where we are in our journey. Are we financially and physically able to keep the cow and continue stewarding it? Or are we better off starting over? That decision is really up to the individual homesteader, the property they have, the finances they have, and what their goals are.

At the end of the day, it’s your choice. Choose well. And sometimes that means keeping the cow and loving it well, or finding the cow a beautiful new home where she will be loved well, not just thrown on the auction block.

The Future of the Homestead Milk Cow

Let’s be honest, Hazel isn’t “tiny”, even though the title says that. It’s a play on words, if you will. However, we have established the fact that she is a much smaller-framed, grass genetics heifer that will function well on this property. She’s not a mini, but she’s not quite a mid-size. And she’s definitely no where close to being a full-size, at all. That was made very evident when we boarded our friend’s full-sized commercial Jersey cow.

Hazel is, however, the future of the homestead heritage milk cow. With the homesteading movement growing by leaps and bounds, homesteaders across the country (and beyond) need an alternative option. But that alternative option actually gets us closer to the original option of the homestead dairy cow. A smaller-framed, more manageable cow that doesn’t tower over you and produce 7 gallons a day. No sir, this heritage homestead milk cow will give you a good 1.5 to 2 gallons per milking, convert sunshine into butter, take up less space on your farm, and still be the most beloved animal you have.

You won’t be fighting with a commercial dairy cow anymore, you’ll be managing a smaller, yet still strong, milk cow and her offspring. Getting back to true Jersey genetics is exciting.

The commercial industry has played with livestock genetics for far too long. What we know now, and continue to learn, is that nothing “commercial” has the homesteader’s best interest in mind. But again, you don’t know what you don’t know. If you think all cows (other than minis) are just massive animals that tower over you, guess again. Fret not, my friend. There is another option. A heritage option. A true “back to the homestead” option with genetics of goodness that is manageable for many homesteads. And I’m excited to see where this journey takes us….

Thank you for reading Amy K. Fewell | Homesteading for the Kingdom. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Leave a Reply